A Hillfort Near You

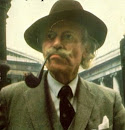

Hillforts pepper our hills; there are possibly as many as four thousand of them. But they are not always on hills and quite probably not always, or even often, forts. That label was pinned on them by Sir Mortimer Wheeler, one of the 20th century’s most revered pre-history pundits and, as a former Brigadier in the Army, he might simply have seen what he was trained to see! Here he is, doing a Gandalf impersonation.

Looking for some basis for the generalisations needed to keep the blog notes short, I visited dozens of them, waded through inscrutable archaeology papers in the British Library, scaled a mound of local landscape history books and tiptoed into the prehistory nerd websites. We need a literary Ozempic for some of this stuff.

Some of the hillforts do seem to have seen conflicts. Cadbury in Dorset saw battles with the Romans. Others seem to have been built with defence in mind, for instance, by adding additional fortifications at the otherwise weaker entrances. Most left no evidence that these were tested but, of course, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

It is possible that some of them might have been used as trading centres with guarded entrances to check (and maybe tax) what was going in and coming out. Or some of the larger efforts might have been status symbols, swaggering constructions like the faux castles you see today. But there are other possible explanations for their location, e.g. proximity to good farmland, water or trade routes. The fact is, we don't really know for sure when they were built, why and by who. Over the centuries, explanatory myths and legends have grown with the weeds around them.

|

| Cadbury |

This is an atmospheric video of Cadbury, which is associated with Arthur’s Camelot as well as the Romans, and which ended its useful life as a Saxon burh. It is a good example.

Link: Cadbury From The Air And if you are gagging for real detail, here is a report with more detail from the History Hit podcast. Link : Cadbury Archaeology

I am averse to some researchers' habit of squeezing sacred symbolism out of anything that can’t be readily explained, but we also have to accept the possibility of some ceremonial or religious shenanigans. It does seem to be the case that around these entrances, you sometimes find more strange stuff lying around than you might expect after a solstice swingers party. For instance, odd corpses, some of which might have been exhumations or sacrifices, hoards, possible votives and the arranged remains of ravens or horses.

A preference has been observed for an east/west alignment of entrances, which might indeed be connected to worship of a Sun God. Famous monuments like Stonehenge and Newgrange in Ireland show that the solar alignments were important. But in lesser places, it might also reflect a simple effort to extend the hours of useful daylight.

Quite a few show evidence of being permanent settlements, with post hole evidence of typical Iron Age roundhouses, but if there is any partial consensus these days, it is the unexciting alternative that many were simply enclosures, used as seasonal gathering places for herders, rather than forts. This might be particularly the case in the Southeast, where the enclosures were typically smaller and less forbidding. Even so, ever the doubter, I ask if their usefulness would be seen as an adequate reward for the hard labour involved in building them.

|

| Evidence-based settlement model |

There are lots of them: See this natty map. Link: British Hillforts Note how many there are to the West and North, and fewer in the east. Maybe that is because the land in the east is flatter and thus provides fewer sites on high ground, or because of cultural differences among tribes. More questions without answers!

Lots of them are small enclosures where the banking wouldn’t have deterred the inlaws, let alone the outlaws. These might also have been more vulnerable to centuries of erosion and later ploughing and levelling or, like Tadmarton Camp in Oxfordshire, dissection by a road and incorporation into a golf course! Sadly, most of the iconic and best understood examples lie outside our area. You would be surprised how few have been properly excavated and studied.

Many don’t look like much now, just bumps in the landscape, but even though the examples in the South East are not particularly big by the standards of places like Cadbury, some are still massive. There is no regular or universal pattern in how they were built. This is unsurprising, given that they are spread all over the country. It is a fact that many seem to have been used, abandoned and reused several times.

|

| Another Evidence-Based Model |

For instance, Maiden Castle in Dorset was the size of fifty football pitches and had a 'ditch to bank' height of over 25m, possibly with a palisade, now long gone, to add more height. Imagine the work involved, especially since they are unlikely to have wanted to waste precious iron on making shovels! I like to think that the No.1 God for the people who built these places, was probably the one who could be summoned to appear at the wheel of a JCB.

|

| Maiden Castle |

|

| Maiden Castle Ramparts (English Heritage) |

Nearer to home, Danebury in Hampshire is much smaller, but has also been thoroughly explored. Evidence points to its lengthy role as a settlement for a few hundred people, probably trading their agricultural produce for metals, etc.

Dating is tricky because places would have been rebuilt over time, and people then were as relaxed about flattening what went before as the people of Tadmarton are today. Most of what is readily visible today originated in the Iron Age, and specifically between 800 BC and the visit of Julius Caesar and in Southeast England, few were used afterwards. But the detritus left behind suggests that the eldest originated much earlier, in the Bronze Age (from 2400 BC), and a few might have been in use earlier still.

Similar enclosures can be found across Europe. You can see the evidence provided by Asterix's village in the pic below. But the stylistic timeline differed. What was being built in England in the Iron Age seems to have already disappeared on the other side of the Channel.

|

| La Ville d' Asterix |

The hillforts didn’t exist in a cultural vacuum. Nearby, you can often find the ancient long barrow tombs, monuments, field patterns, boundaries, causeways, cursus and whatnot, which are often even more mysterious. They are easiest to detect from the air by a specialist with wit and kit. Good examples are Maiden Bower near Dunstable and Blewburton Hill in Oxfordshire, a cursus outside Dorchester on Thames. Don’t bother visiting the latter, there is nothing to be readily seen!

In the Southeast, the

most visible hillforts are strung along the chalk scarps. But there

are also some significant (and probably later) Iron Age enclosures on

the lower ground. These ‘Oppida’ were the nearest thing that the

Iron Age tribes had to urban sophistication and hadn’t been around

for long when the Romans arrived and, in some cases, took them

over. A good example is Silchester, where a few low mounds that

are the remains of the Atrebates settlement are dwarfed by the scale

and remaining walls of the Roman town that followed and absorbed it.

(That one is certainly worth a visit!).

In what follows, I

will give a quick roundup of the most visible examples in the area.

In some cases, where they feature on one of my cycle routes, you will

find more details in the Waypoint notes here : www.pootler.co.uk .

There

is a string of hillforts along the North Wessex Downs section of the

Ridgeway, between Swindon and Goring, which illustrate the variety.

They are Liddington, Uffington, Rams Hill and Segsbury.

Liddington Castle might have been started in the late Bronze Age, and was deserted and then reoccupied in Roman times and added to again after the Saxons arrived. There is no sign of military use even though the impressive ramparts appear to have once been revetted with timber.

|

| Liddington Ramparts |

Uffington, which is next to the famous White Horse, is also an impressive size. It would have had two timber retaining walls, separated by a ditch filled with earth and rubble. It appears to have been in continuous use until shortly before the Romans turned up.

Between Liddington

and Uffington, in a hollow in the hills, there is a small enclosure

called Alfred’s Castle, which is unlikely to have had anything to do

with Arthur and presents a homely contrast with roundhouses, pits for

grain and evidence of metal working and pottery. It lasted from the

late Bronze Age, and the Romans later used the site for a villa/farm.

|

| Uffington, in the background |

Rams Hill had a single timber-framed wall, and although it seems to have started life as a defensible space, it might have been superseded by nearby Uffington and ended up mainly an enclosure rather than a fort. It sits amid a larger-than-usual collection of burial mounds. Maybe that is significant. Perhaps the food was really bad. Who knows. Now it falls into the ‘blink and you will miss it’ category.

Segsbury seems to have been enclosed by a ditch before the ramparts were added and seems to have declined while nearby Uffington was still in use. Maybe they were built by the same people for different purposes. It has been suggested that it might have fallen out of use because people started to raise cattle rather than sheep, while Uffington retained a wider religious or ceremonial role. There is more information and a very short flyover video of it here: Link : Segsbury Castle

To the North, Membury Camp sits on a small plateau below the scarp and is presumably located to make good use of access to Membury Services on the M4. While it is wooded, the earthworks are impressive once you find them, even though they have been damaged in places by the adjacent RAF base.

Facing these, on the limestone hills across on the other side of the Vale of the White Horse, were some much smaller enclosures, possibly just banks with a fence on top and used on an occasional basis, perhaps in connection with the sheep farming.

On the Southern side of the Wessex Downs, Walbury near Inkpen Beacon covers 33 ha. It hasn’t been researched and only has a single bank, but it is spectacularly located and well preserved.

|

| Walbury |

In Buckinghamshire, there are quite a few, more varied and scattered. Desborough in West Wycombe and Cholesbury near Tring were built in the late Iron Age and seem to have still been in use when the Roman Galleys appeared on the horizon. Cholesbury is a 6 ha enclosure with wooded ramparts on high ground in the village. I assume that, if the enclosure was intended for defence, the ground must have been open when it was built. Or maybe it simply served to mark the settlement or to keep animals in or out. Although there is some evidence of iron working, it doesn’t generally seem to have been made much use of, maybe because of the lack of a water supply. This must have been a common problem on the chalk hills.

|

| Cholesbury |

In contrast, enclosures at Ivinghoe, Taplow, Boddington and Medmenham might date to the late Bronze Age, almost a millennium earlier.

Tree cover is an issue with many of these relic settlements, not just because they now hide what’s there, but also because the growth can damage the ramparts. Desborough Castle (in Wycombe) is an example. Pulpit Hill above Great Kimble and Boddington near Wendover are others. In each case, once you get into the trees, the banks are visible but not very impressive.

Incidentally, if you are walking the Ridgeway between Wendover and Princes Risborough, or dropping in on the Prime Minister at Chequers, don’t be fooled by Cymbeline’s Castle near Pulpit Hill. It looks like it should be a hill fort, and the legend is supportive, Cymbeline is associated with the Iron Age British chieftain Cassivellaunus, who the Romans fought and defeated in AD 54, but it is actually the site of a medieval Motte & Bailey. Nearby Pulpit Hill is the real McCoy, but although marked, it is small and wooded.

To the East, bits left by the inhabitants have been found in most places, but only Ivinghoe has really been studied intensively, maybe because of its location. The view is good, and some useful information was gleaned about the physical features. But the remains were unimpressive, just a sword and a few bits of skull. Here is a link to the English Heritage Report in case you want more. (Gimme sympathy! In preparing this blog series, I have gone through hundreds of these!!) Link: Ivinghoe Beacon Archaeology

One plus is a good view of the place where the Death Star crashed. Baffled? See my post here: Tinseltown

| Ivinghoe Beacon |

Elsewhere, there are numerous places where archaeology points to ancient settlements which are now invisible. Some are probably lying beneath the back gardens of Aylesbury, so I am not interested. Move along there.

As you go east into Hertfordshire, the chalk hills shrink away and the number of prominent sites diminishes with them. Ravensburgh (north east of Luton, and which sits on private land) is about 9 ha. with a single bank and ditch. It was a comparatively late effort; the site had been farmed until it was built around 400 BC and refortified around 50BC. There are signs that there might have been conflict there, and it is one of several candidates for the location for Cassivellaunus' supposed ‘last stand’ against the Romans.

I have already referenced Cymbeline's Castle in this connection, and a settlement at Wheathampstead also lays claim to this ignoble comeuppance. It reminds me of the numerous claims to be the original Camelot, and wouldn’t you just know it, some associate Cassivellaunus with Arthur. His ghost was photographed there. Or maybe I lifted the graphic from the 'Assassin's Creed' video game.....You decide.

Other spots that have been thought of as hillforts are less impressive and demonstrate how legend can supersede the facts. ‘The Aubreys’ (Redbourn) was in use in Roman times, and while the name might mean ‘fortified place’, there is no evidence that there was any fighting there. The site has been mangled by subsequent development. Sharpenhoe is close to Ravensburgh, but this might not be a hillfort, but just a result of the proliferation of rabbit warrens!

Many of the known settlements are now thought to have been, not so much forts, as loose and sprawling centres for artisans and traders. Many of the sites don’t seem to have much defensive potential; the extent of Iron Age trade is often underestimated, and perhaps routes of travel and trade dictated their location. St Albans is an example, and the Atrebates settlement at Silchester and the Catuvellaunis at Wheathampstead might be others. The pic below is the Dyke Hills on flat ground next to the Thames at Dorchester, which was the late Iron Age border between those two tribes. It was hardly impregnable!

|

| Calleva Atrebatum: Pre Roman Oppida |

|

| Dyke Hills : Dorchester on Thames |

My blog is mostly about what shapes our places and landscapes. For the past ten thousand years, people have played their part, but the fact is that we are fairly clueless about what was going on during a lot of that time. In summary, when it comes to hillforts, the best I can do to settle my restless curiosity is a guess.

With the smaller enclosures the consensus is that they played a role in the farming economy and husbandry in particular. Determining the role of the larger ones is a greater challenge. They might have had a different purpose in different places and, given that they evolved over a couple of millennia, this might have changed over time. Some seem to have been simply settlements, but in a few cases they may have accommodated a large permanent population. The long walls of the largest would have taken a lot of manpower to defend simply because an attacker would have more scope to concentrate forces and shift the point of attack.

Even though the evidence isn't readily visible, we know that many of them stood in wider, well populated farming communities. So my supposition is that they probably provided a measure of deterrence, a base for the local panjandrum and maybe his close family and mates and, if there was a threat, a rallying point and place of refuge for people and livestock.

The examples in the Southeast are mostly unprepossessing. Further west, Cadbury and Maiden offer nore to the eye. But do offer a pleasant, windy walk and, most importanly, a sense of wonder at their sheer antiquity and wonder at the lives of the people who might have once have built and lived in them. And while it might be more accurate to refer to many of them as simply banked enclosures, I will continue to use ‘hillforts’ in the same way as we understand a lion to be more than just an oversized moggy. What good would it do, if sunny certainties dissipated the clouds of ignorance? Maybe if we knew more about them, they would lose some of their magic.

So there you have it. Visit them for the air, take in the views and the indistinct whispering of ancient history; then come away without anything near a definitive view of what actually went on. If there was, the magic would disappear.